THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO HEARTRATE MONITORING

Although Heart-rate monitors (HRM’s) are a common item in most athletes’ kit bags these days, very few people know how to get the best out of them. Many athletes have little idea what the numbers they see actually mean. Some wear their monitor yet completely ignore it, whereas others totally rely on their heart-rate data and forget other key information. Very simply, HRM’s are there to help guide the intensity of your workout. To train specifically and correctly, you’ll need to train in carefully defined “zones”. This article assumes that you already have your zones but need practical pointers on how to use your HRM out on the road. What follows is a brief discussion on some of the factors affecting heart-rate and the remedies you can apply.

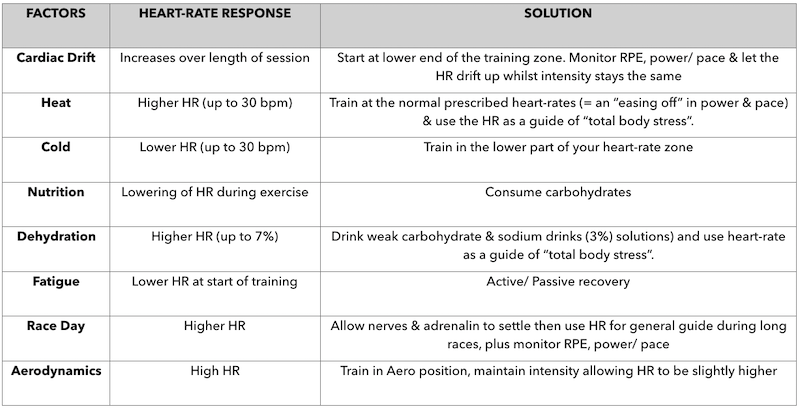

After prolonged exercise at moderate intensities in a normal or warm environment, heart-rate will often rise despite no felt increase in intensity. This is called “Cardiac Drift” and can produce heart-rates up to 20 beats per minute higher than early session heart-rates. The cause is core temperature increase. Here heart-rate does not offer a true reflection of intensity so in this case heart-rate is best used in conjunction with power (on the bike) or pace (on the run) and/ or perceived exertion. The remedy is to start at the lower end of your training zone and over the course of the session allow the heart-rate ro rise up through and slightly above the upper limit of the target heart-rate zone whilst holding constant intensity.

In cold weather, there may be an increase in oxygen uptake with heart-rates staying similar to those of normal conditions. In this case, the body is working harder but this is not shown in the bpm’s on your monitor. Here heart-rate underestimates the intensity. The take home lesson is to train in the lower portion of the prescribed training zones. Hot weather gives much higher heart-rates than usual. This is due to the core temperature increase as discussed in cardiac drift plus the increase in environmental temperature. Increases of between 10 and 30 bpm have been reported in the heat, with no change in actual intensity (watts/ speed). Here again, Heart-rate is not reflecting the true intensity. In this case, the bpm’s shown over-estimate the workload. However, the higher heart-rate is indicative of a higher total body stress as the body works harder to cool and maintain homeostasis. Even though the intensity of a work bout in the heat is not a high as in normal weather, the stress the body is under is increased. Therefore, train at the normal prescribed heart-rates (which will mean an “easing off” in power and pace) and use the heart-rate as a guide of “total body stress”.

Nutrition and calorific intake is critical especially for the long distance athletes. During racing, a lowering of the heart-rate in conjunction with an increase in the perceived effort means that you need to take in calories. In this case, the heart-rate monitor serves as your blood sugar level monitor and saves you from the much dreaded “bonk”. If you find that your heart-rate won’t rise to normal levels early on during training sessions, it’s a good sign of underlying fatigue, especially if your legs feel heavy. In this scenario, cyclists typically find that they are pushing huge race pace gearing but the heart-rate says otherwise. Here you have two choices. Either back off the pace and do a shorter active recovery session or head home for passive recovery.

Dehydration is a common phenomena especially but not solely in the heat. Here the blood plasma volume drops and the heart-rate increases as cardiac output rises. The bpm rise may be between 2 and 7% (that’s up to 160 bpm from 150 bpm). The remedy here is obviously to drink, but also to use heart-rate as a guide of “total body stress”.

For Cyclists and Triathletes, as you strive to make your time-trial position more aerodynamic you may find that your heart-rate at a given intensity has risen. Many think that this means that the new lower position is counter-productive. This is not necessarily so. Research shows that both oxygen uptake and heart-rate are higher in the “aero” position than the standard road position. This is attributed to the increased contribution of the shoulder muscles & a less efficient hip angle. The costs in heart-rate are considered negligible compared to the time savings of improved aerodynamics. Although the heart-rate may be up by 2-5 bpm, it is not a true reflection on intensity so you can allow your heart-rate this “drift” when on the aero-bars, knowing that there has been no real increase in effort. The key here is to train in your aero position & be aware of how it affects you. As long as you can maintain an efficient pedal stroke and cadence and as long as your breathing mechanics are not compromised, the aero position is the way to go for faster times despite the small bpm increase.

On race day, you may find that your heart-rate is up at high levels even when you are warming up. Here the heart-rate is exaggerating the intensity and the adrenalin coursing through your veins is responsible. For Triathletes, they often find that the heart-rate is elevated early on during the bike ride after going from a horizontal position during the swim to upright running then transitioning to the bike. The key here is to train for this transition, but in both these cases the real answer is to wait until you are settled and some time (30mins+) in to your race to let your heart-rate settle down and give you more honest readings. Furthermore, it has been shown that athletes can achieve higher heart-rates during race situations than during training sessions even though the intensity, power or speed produced has remained the same. These race day heartrates again over-estimate the intensity. In all these cases, perceived exertion is a useful tool to use in conjunction with your heart-rate. For short races, I suggest forgetting your HRM completely unless you are recording the bpm to analyze later. For long races, the HRM has many benefits listed throughout this article. In racing conditions often it is your gut instinct that will tell you hard you should go with your HRM providing back-up information and real-time data on the current stresses and conditions you are facing.

The most important message for you to take away from here is that, HRM’s are a great tool but they are best used in conjunction with other information. Heat, dehydration, bike position, biomechanics and day to day biorhythms all affect the numbers you see and some of these affect the intensity you feel. Taking into account all the factors allows you to further maximize your training and take your performance to even higher levels.